A break-out city-building success.

Nothing turns a soul dark like a great strategy game. When I started playing Prison Architect, I tried to make a well-maintained, comfortable place to pass a decade or two in quiet contemplation. I gave my prisoners televisions. I gave them sofas. They responded with fire and riots and scheming while the guards’ backs were turned. Well. Things aren’t so pleasant any more.

Prison Architect isn’t a game that shoots for absolute realism by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s one of the most detailed small-scale simulators that you’re ever likely to play. A prison is after all essentially a self-reliant city – a contained ecosystem where the wheels have to keep turning, zoomed in to the point that every citizen, every water pipe, matters.

We want to hear it.

Prison Architect doesn’t skimp on any of that detail. You don’t just put down buildings, but plan them.

Prison Architect doesn’t skimp on any of that detail. You don’t just put down buildings, but plan them (in a way that feels incredibly fiddly to begin with and will lead to a lot of buildings ending up the wrong size for what you need as you figure it out), zone out individual rooms, and kit them out with what they need. Everything in one big building? Lots of small buildings around a yard? The system allows both, as well as drawing a line between essentials for each room, such as a toilet, and whatever generous extras you feel like providing, such as windows in basic cells or beds in solitary confinement.

All this makes for a surprisingly open sandbox, given the highly specific nature of the job, though it’s a sandbox where the map has to be fenced off quickly, before the first prisoner delivery arrives. The catch, paving the road to Hell with former good intentions, is that you’re running a private prison, which has to turn a profit in addition to processing criminals. That’s not too difficult early on, but the needs of a larger prison soon multiply. Buildings. Staff. Disaster recovery. It goes on. It’s not enough for instance to just put down CCTV monitors; they all have to be hooked up to a console with a guard assigned to watch, otherwise you’re still blind to what prisoners are up to.

While I say “not too difficult” though, I’m speaking relatively. Prison Architect does a dismal job of introducing itself if you just start playing, and just getting a handle on the basics can be incredibly frustrating. Start up the sandbox and you get very little to go on – a field, very little money, and a welcome letter with only the most casual introduction.”

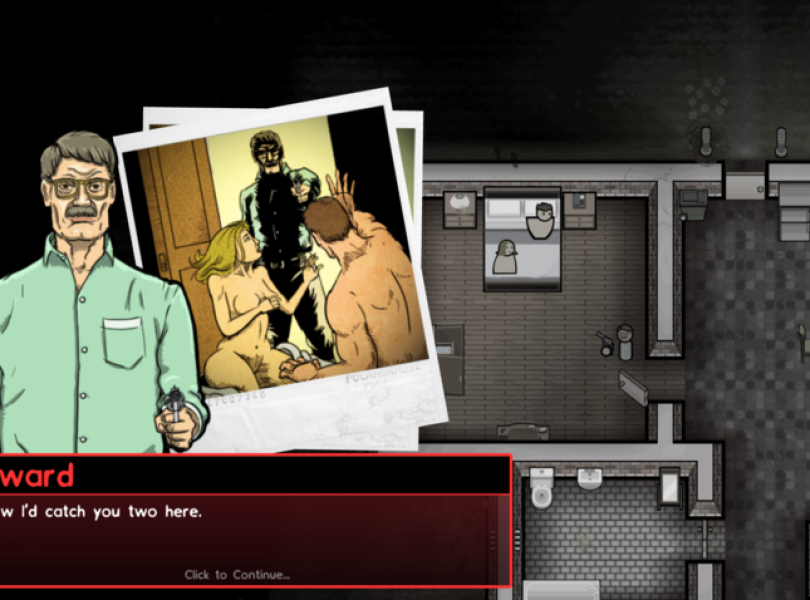

The tutorial takes the form of a five part mini-campaign that does cover the basics, but more often gets carried away showing off the ‘fun’ stuff like how to set up an electric chair or handle a riot, when what a new player really needs to know are things like why the prisoners aren’t able to go to the canteen, when to start work on the Administration building, or that Grants are essentially the mission system that provide the money and steps rather than an advanced game feature. The details get lost in the storytelling, with the result that it’s easy to become blind to key things like being able to switch off the intake to avoid having murderers twiddling their thumbs by the side of your road.

To get started, you almost have to rely on wikis and often out of date guides, which is all the more frustrating because most of Prison Architect’s early game isn’t that complex. Later, when you start juggling dedicated guard patrols (anything they can’t see is hidden by Fog of War, just for starters) and handling prisoner psychology and attempting to reform instead of merely incarcerate them, that changes, and that’s fine. Throughout though, alerts and tooltips can be maddeningly vague about what things actually are and do and what rooms they’re intended to be put into.

Something like a fire or a riot is just as disastrous as it should be.

The complexity is ultimately in Prison Architect’s favour though, with much of the challenge coming from knowing what you need to do, but only being able to afford it by cutting corners and thus creating problems for yourself later on. Optional Events mix things up even more, forcing you to scramble to throw together something, anything, to handle incoming trouble, with something like a fire or a riot being just as disastrous as it should be – hopefully existing security systems lock things down, but then you summon riot teams and armed police to quell the problem in very, very simple RTS style. There’s also a decent amount of scope for personalisation in terms of materials and possible layouts, as well as modding support via Steam Workshop, that all helps make the experience far more than just Boring Grey Box Simulator 2015.

On top of the basic sandbox, there are two modes to play – that short campaign mode mentioned earlier, and Escape Mode, where you control a prisoner in either your own prison or random/subscribed ones from the Steam Workshop. Campaign is an odd mix of narrative and tutorial that’s mildly diverting, but neither particularly compelling in terms of the story it tells between telling you to build things, nor well judged in the order it covers crucial systems. I’d have preferred those vignettes to be part of the sandbox really, and a proper intro put in their place.

Escape Mode can best be summed up by the fact that it’s in the Extras menu. It’s cute, but if you want that experience, play The Escapists (Review) instead. It’s a very simple game where you fight people to level up, recruit other prisoners, and regularly get let down by the maps. In the first one I tried, I ended up locked in a Holding Room forever. In the second, no guards showed up, and I was able to just walk away – or rather, into the invisible barrier at the map edge. The third and fourth worked, but only just showcase the incredibly weak combat and kill any remaining interest.

Luckily, the sandbox is more than enough to carry Prison Architect. However long the appeal of building prisons instead of cheerier things like theme parks lasts, developer Introversion’s attention to detail and the depth of its focus makes for both a satisfying challenge and a fascinating simulation. Plus, if you need another reason to never, ever want to find yourself behind bars, you’ll soon find an appreciation for the mathematics of suffering right up there with anything in The Shawshank Redemption.

After a poorly handled start, Prison Architect becomes one of the most in-depth, satisfying builder games in a long time. It’s a shame the non-sandbox options aren’t better, and the nature of the simulation inherently lacks the joy and beauty of other subjects, but few other games have done such a good job at capturing not just the nature of the job they simulate, but also the mindset required to do it ‘properly’.