Like the spartan sheen of its digital environments, Volume is stealth gameplay at its most fundamental level. It’s a fine-tuned equation, and aside from several threatening variables, not much can upset its balance.

Volume is a cyberpunk retelling of the classic Robin Hood legend. It takes place in simulations filled with labyrinthine corridors and enemy guards, wherein our hero Rob Locksley broadcasts hypothetical heists against corrupt corporations. There are trip lasers, alarm panels, and automated turrets. It’s your job not only to navigate these hazards, but also collect a varying number of floating gems, which will unlock an exit portal placed somewhere in the environment. Imagine Solid Snake, of Metal Gear fame, thrown into Pac-Man, with only a few gadgets and his bare hands to help him survive.

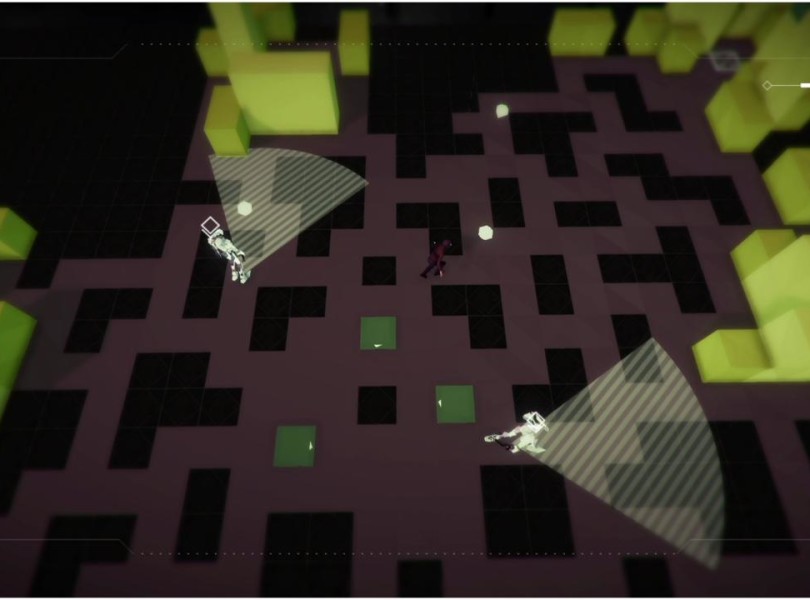

All of this sneaking and collecting is done from an overhead, isometric angle, which lets you see around corners and over looming walls. Guiding the character through these booby-trapped mazes is as much about careful traversal as patient observation. And observation is important, because Volume is just as much a puzzle game as it is a member of the stealth genre.

Most levels don’t leave room for improvisation, instead guiding you with visual cues and subtle hints toward the exit. The fun in Volume doesn’t lie in choosing your favorite approach, but discovering the few that finally work. I remember one maze, about halfway through Volume’s campaign, which took me longer than usual. Guards lined either side of a central hallway with low walls, so walking straight through wasn’t possible. But in one of Volume’s more subversive moments, I set off the alarm on purpose–by luring every guard to one side, I opened up the opposite for a quick escape. Those last few steps before the exit were pure bliss–not just a daring escape, but a victory lap as well.

These environments, and the puzzles they place before me, showcase expert pacing that makes me want to keep playing, over and over again. Although there are some difficult rooms here, I never once felt bogged down. New enemy types with different vision cones and various patrol patterns made me adapt on the fly, and force fields erased routes I once thought passable. I was always ready for the next challenge, whether it required quick footwork, measured advances, or creative use of Volume’s multifarious gadgets.

These tools are further proof of Volume’s ingenuity. There’s a distraction gadget you can attach to walls; a cloning device that sends out doppelganer projections; and a trip wire that stuns unsuspecting enemies. One item even makes you invisible for a few seconds–but only a few. These pickups aren’t just hints at how to navigate the level, but useful tools that change the way you observe the environment.

These simulations have a clean, simple visual vocabulary, which never leaves anything open to interpretation. It places function over form, and by definition, that’s good design. Guards’ vision cones are always visible, electrified tiles are apparent, and lasers emit a bright white streak. The latter can lead to frustrating restarts, as your character sometimes keeps moving after you let go of the computer key or analog stick. Setting off alarms because the controls resisted my intentions would have been a bigger problem if it weren’t for the intelligent checkpoint system.

These holograms are clearly marked, and I never worried where failing might send me back to. This is a subtle tweak with obvious repercussions: I often strayed from my intended route just to touch these floating waypoints, knowing I might set off an alarm in a subsequent hallway. These safety nets, coupled with the floating gems necessary for completion, took me out of my comfort zone, thereby lending some risk to the equation.

Even Volume’s audio cues emit a white circle. Using these to manipulate guards is essential, and luring them from their positions is a only a matter of whistling, or using sound-emitting gadgets in their vicinity. The white circles never leave any doubt as to whether guards would hear me or not. Ironic as it is in a game called Volume, I could have finished it with the sound turned off.

In dissecting the campaign from my perspective as a player, I’ve ignored one of Volume’s more compelling features. It has level-editing tools that are simple, streamlined, and accessible. And after only an hour of experimentation, I created a map that was somewhat challenging. It wasn’t on par with the campaign’s inventive levels, but the short time it took me to create it was telling: like the simulations in Volume, its editing tools are all about function, and uploading maps for others to play is just as easy.

These levels won’t tell the story the campaign does–but that’s for the better.

Volume’s narrative attempts broad social commentary on the modern internet environment, where people brand their own personalities in a digital limelight. In one moment of levity, a character receives criticism for naming his company after himself–clearly Volume developer Mike Bithell making a self-aware jab. Meanwhile, protagonist Locksley streams his heists to thousands of followers, accruing enough to threaten the overarching corporate structure and make enemies in high places. By broadcasting his mock heists, Locksley is making futuristic Let’s Play videos for the masses.

But while Volume does analyze the modern landscape of online content, it does so with a fragmented and intrusive narrative, and it doesn’t end up saying much. Before I turned subtitles off in the main menu settings, they covered important aspects of the levels, such as alarm panels and guard vision cones. Even after I disabled the text boxes, characters repeated monologues ad nauseum when I restarted from checkpoints. Some characters even spoke for the duration of shorter missions, removing me from the tense stealth gameplay in a jarring way.

These characters are portrayed extremely well, with voice acting to match: Andy Serkis–from the Lord of the Rings trilogy– plays the villain Gisborne, and he paints the picture of a disturbed, greedy corporate mogul. But Volume’s characters inhabit a disjointed story that I don’t find necessary. Aside from the bookend videos, there’s one cutscene exactly two-thirds of the way through the story. The reimagined Friar Tuck also appears for only two of the campaign’s 100 missions, like an actor who wandered on-stage before realizing he was at the wrong play. These pieces of exposition and characterization feel forced, as if they don’t belong.

But when you’re able to avoid the barrier the overarching narrative creates, Volume flows from one level to the next with the aptitude of a great stealth game, and the inventiveness of a clever puzzle title. It stumbles when trying to tell a story, but excels at communicating phenomenal mechanics.